search this blog

Thursday, May 31, 2018

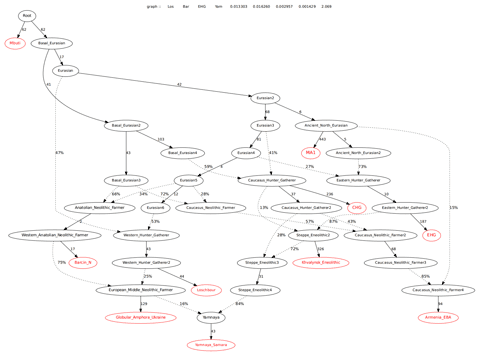

What's Maykop (or Iran) got to do with it? #2

For the past few days I've been trying to copy and also improve on the qpGraph tree in the Wang et al. preprint (see here). I've managed to come up with a new version of my model that not only offers a better statistical fit, but, in my opinion, also a much more sensible solution. For instance, the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer node now shows 73% MA1-related admixture, which, I'd say, makes more sense than the 10% in the previous version. The relevant graph file is available here.

Samara Yamnaya can be perfectly substituted in this graph by early Corded Ware samples from the Baltic region (CWC_Baltic_early) and a pair of Yamnaya individuals from what is now Ukraine. This is hardly surprising, considering how similar all of these samples are to each other in other analyses, but it's nice to see nonetheless, because I think it helps to confirm the reliability of my model.

And yes, I have tested all sorts of other Yamnaya-related ancient and present-day populations with this tree. They usually pushed the worst Z score to +/- 3 and well beyond, probably because they weren't similar enough to Yamnaya. But, perhaps surprisingly, Bell Beakers from Britain produced a decent result (see here).

See also...

Yamnaya: home-grown

Ahead of the pack

Late PIE ground zero now obvious; location of PIE homeland still uncertain, but...

Friday, May 25, 2018

Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups may have led to the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck (Zeng et al. 2018)

A very interesting paper has just appeared at Nature Communications that potentially offers an explanation for the well documented explosions of certain Y-chromosome lineages in the Old World after the Neolithic, such as those that led to most European males today belonging to Y-haplogroups R1a and R1b (LINK). I might have more to say about this paper in the comments below after I've read it a couple of times. Emphasis is mine:

In human populations, changes in genetic variation are driven not only by genetic processes, but can also arise from cultural or social changes. An abrupt population bottleneck specific to human males has been inferred across several Old World (Africa, Europe, Asia) populations 5000–7000 BP. Here, bringing together anthropological theory, recent population genomic studies and mathematical models, we propose a sociocultural hypothesis, involving the formation of patrilineal kin groups and intergroup competition among these groups. Our analysis shows that this sociocultural hypothesis can explain the inference of a population bottleneck. We also show that our hypothesis is consistent with current findings from the archaeogenetics of Old World Eurasia, and is important for conceptions of cultural and social evolution in prehistory. ... If the primary unit of sociopolitical competition is the patrilineal corporate kin group, deaths from intergroup competition, whether in feuds or open warfare, are not randomly distributed, but tend to cluster on the genealogical tree of males. In other words, cultural factors cause biases in the usually random process of transmission of Y-chromosomes, increasing the rate of loss of Y-chromosomal lineages and accelerating genetic drift. Extinction of whole patrilineal groups with common descent would translate to the loss of clades of Y-chromosomes. Furthermore, as success in intergroup competition is associated with group size, borne out empirically in wars [43] as ‘increasing returns at all scales’ [44], and as larger group size may even be associated with increased conflict initiation, borne out in data on feuds45, there may have been positive returns to lineage size. This would accelerate the loss of minor lineages and promote the spread of major ones, further increasing the speed of genetic drift. In addition, the assimilation of women from groups that are disrupted or extirpated through intergroup competition into remaining groups is a common result of warfare in small-scale societies [46]. This, together with female exogamy, would tend to limit the impact of intergroup competition to Y-chromosomes. ... Figure 6 shows a striking pattern of differences in shallowness of coalescence in samples from hunter-gatherer, farmer and pastoralist cultures. While hunter-gatherer Y-chromosomes from the same culture, and often the same sites, commonly divide into haplotypes that coalesce in multiple millennia, Y-chromosomes of samples from farmer and pastoralist cultures are more homogeneous and have more recent coalescences. The Bell Beaker culture has a high proportion of sampled males (81%) from a large geographical area (Iberia to Hungary) who belong to an identical Y-chromosomal haplogroup (R1b-S116), implying common descent from a kin group that existed quite recently. Some groups of males share even more recent descent, on the order of ten generations or fewer [64]. Such recent common descent may even be retained in cultural memory via oral genealogies, such as among descent groups in Northern and Western Africa, whose members can trace descent relationships up to three to four centuries before the generation currently living [40]. Likewise, from Germany to Estonia, the Y-chromosomes of all Corded Ware individuals sampled, except one, belong to a single clade within haplogroup R1a (R1a-M417) and appear to coalesce shortly before sample deposition. Thus, groups of males in European post-Neolithic agropastoralist cultures appear to descend patrilineally from a comparatively smaller number of progenitors when compared to hunter gatherers, and this pattern is especially pronounced among pastoralists. Our hypothesis would predict that post-Neolithic societies, despite their larger population size, have difficulty retaining ancestral diversity of Y-chromosomes due to mechanisms that accelerate their genetic drift, which is certainly in accord with the data. The tendency of pastoralist cultures to show the lowest Y-chromosomal diversity and the shallowest coalescence would also be explained, as they may have experienced the social conditions that characterized cultures of the Central Asian steppes [42]. Indeed, the Corded Ware pastoralists may have been organized into segmentary lineages [65], an extremely common tribal system among pastoralist cultures, including those of historical Central Asia [66].Citation... Zeng et al., Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck, Nature Communicationsvolume 9, Article number: 2077 (2018) doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04375-6 Update 30/05/2018: For those clued in, here's an awesome quote from the relevant press release.

The outlines of that idea came to Tian Chen Zeng, a Stanford undergraduate in sociology, after spending hours reading blog posts that speculated - unconvincingly, Zeng thought - on the origins of the "Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck," as the event is known.See also... Late PIE ground zero now obvious; location of PIE homeland still uncertain, but...

Thursday, May 24, 2018

What's Maykop (or Iran) got to do with it?

I had a go at imitating this qpGraph tree, from the recent Wang et al. preprint on the genetic prehistory of the Caucasus, using the ancient samples that were available to me. I'm very happy with the outcome, because everything makes good sense, more or less. The real populations and singleton individuals, ten in all, are marked in red. The rest of the labels refer to groups inferred from the data.

However, this is still a work in progress, and, if possible, I'd like simplify the model and also get the worst Z score much closer to zero. If anyone wants to help out, the graph file is available HERE. Feel free to post your own versions in the comments, and I'll run them for you as soon as I can.

Update 31/05/2018: I've managed to come up with a new version of my model that not only offers a better statistical fit, but, in my opinion, also a much more sensible solution. For instance, the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer node now shows 73% MA1-related admixture, which, I'd say, makes more sense than the 10% in the previous version. The relevant graph file is available here.

For more details and a discussion about the updated model, including additional trees with Baltic Corded Ware and British Beaker samples, please check out my new thread on the topic at the link below.

What's Maykop (or Iran) got to do with it? #2

Citation...

Wang et al., The genetic prehistory of the Greater Caucasus, bioRxiv, posted May 16, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/322347

See also...

Yamnaya: home-grown

Ahead of the pack

Late PIE ground zero now obvious; location of PIE homeland still uncertain, but...

Wednesday, May 23, 2018

More Botai genomes (Jeong et al. 2018 preprint)

Over at bioRxiv at this LINK. Actually, these may or may not be the same Botai genomes that have already been published along with Damgaard et al. 2018 (see comments below for the discussion about that). Here's the abstract. Emphasis is mine:

The indigenous populations of inner Eurasia, a huge geographic region covering the central Eurasian steppe and the northern Eurasian taiga and tundra, harbor tremendous diversity in their genes, cultures and languages. In this study, we report novel genome-wide data for 763 individuals from Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Mongolia, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. We furthermore report genome-wide data of two Eneolithic individuals (~5,400 years before present) associated with the Botai culture in northern Kazakhstan. We find that inner Eurasian populations are structured into three distinct admixture clines stretching between various western and eastern Eurasian ancestries. This genetic separation is well mirrored by geography. The ancient Botai genomes suggest yet another layer of admixture in inner Eurasia that involves Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe, the Upper Paleolithic southern Siberians and East Asians. Admixture modeling of ancient and modern populations suggests an overwriting of this ancient structure in the Altai-Sayan region by migrations of western steppe herders, but partial retaining of this ancient North Eurasian-related cline further to the North. Finally, the genetic structure of Caucasus populations highlights a role of the Caucasus Mountains as a barrier to gene flow and suggests a post-Neolithic gene flow into North Caucasus populations from the steppe.Jeong et al., Characterizing the genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia, Posted May 23, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/327122 See also... New PCA featuring Botai horse tamers, Hun and Saka warriors, and many more...

Global25 workshop 2: intra-European variation

Even though the Global25 focuses on world-wide human genetic diversity, it can also reveal a lot of information about genetic substructures within continental regions.

Several of the dimensions, for instance, reflect Balto-Slavic-specific genetic drift. I ensured that this would be the case by running a lot of Slavic groups in the analysis. A useful by-product of this strategy is that the Global25 is very good at exposing relatively recent intra-European genetic variation.

To see this for yourself, download the datasheet below and plug it into the PAST program, which is freely available here. Then select all of the columns by clicking on the empty tab above the labels, and choose Multivariate > Ordination > Principal Components.

G25_Europe_scaled.datYou should end up with the plot below. Note that to see the group labels and outlines, you need to tick the appropriate boxes in the panel to the right of the image. To improve the experience, it might also be useful to color-code different parts of Europe, and you can do that by choosing Edit > Row colors/symbols. Of course, if you have Global25 coordinates you can add yourself to the datasheet to see where you plot. Components 1 and 2 pack the most information and, more or less, recapitulate the geographic structure of Europe. However, many details can only be seen by plotting the less significant components. For instance, a plot of components 1 and 3 almost perfectly separates Northeastern Europe into two distinct clusters made up of the speakers of Indo-European and Finno-Ugric languages. This plot might also be useful for exploring potential Jewish ancestry, because Ashkenazi, Italian and Sephardi Jews appear to be relatively distinct in this space. Thus, people with significant European Jewish ancestry will "pull" towards the lower left corner of the plot. For example, someone who is half Ashkenazi and half German will probably land in the empty space between the Northwest Europeans and Jews. See also... Global25 workshop 1: that classic West Eurasian plot Global25 workshop 3: genes vs geography in Northern Europe Global25 workshop 4: a neighbour joining tree Getting the most out of the Global25 Genetic ancestry online store (to be updated regularly)

Monday, May 21, 2018

Global25 workshop 1: that classic West Eurasian plot

In this Global25 workshop I'm going to show you how to reproduce the classic plot of West Eurasian genetic diversity seen regularly in ancient DNA papers and at this blog (for instance, here). To do this you'll need the datasheet below, which I'll be updating regularly, and the PAST program, which is freely available here.

G25_West_Eurasia_scaled.datDownload the datasheet, plug it into PAST, select all of the columns by clicking on the empty cell above the labels, and go to Multivariate > Ordination > Principal Components. Here's a screen cap of me doing it: This is what you should end up with. Please note that I also ticked the "convex hulls" box to define the populations from the "group" column in the datasheet. Here I also ticked the "group labels" box. It's generally a useful feature, even though it makes a mess of the plot in this case due to the large number of populations. See also... Global25 workshop 2: intra-European variation Global25 workshop 3: genes vs geography in Northern Europe Global25 workshop 4: a neighbour joining tree Getting the most out of the Global25 Genetic ancestry online store (to be updated regularly)

Wednesday, May 16, 2018

On the genetic prehistory of the Greater Caucasus (Wang et al. 2018 preprint)

Finally, the focus shifts to the Eneolithic/Bronze Age North Caucasus. In a new manuscript at bioRxiv, Wang et al. present genome-wide SNP data for 45 prehistoric individuals from the region along a 3000-year temporal transect (see here). From the preprint (emphasis is mine):

Based on PCA and ADMIXTURE plots we observe two distinct genetic clusters: one cluster falls with previously published ancient individuals from the West Eurasian steppe (hence termed ‘Steppe’), and the second clusters with present-day southern Caucasian populations and ancient Bronze Age individuals from today’s Armenia (henceforth called ‘Caucasus’), while a few individuals take on intermediate positions between the two. The stark distinction seen in our temporal transect is also visible in the Y-chromosome haplogroup distribution, with R1/R1b1 and Q1a2 types in the Steppe and L, J, and G2 types in the Caucasus cluster (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Data 1). In contrast, the mitochondrial haplogroup distribution is more diverse and almost identical in both groups (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Data 1).Thus, the most important "Indo-European" Y-haplogroups today, R1a-M417 and R1b-M269, did not arrive in Europe from the Caucasus or Near East. They're native to Europe. Hence, it appears that Eneolithic/Bronze Age Eastern Europeans mostly acquired their Near Eastern-related ancestry via female exogamy from populations in the Caucasus. That's basically what I've been arguing for a few years now. It feels good to be vindicated, especially considering the unfair criticism that I was subjected to here and elsewhere because of expressing this opinion (for instance, see here). However, as far as I can see, based on the samples in this preprint, neither the Caucasus Maykop nor steppe Maykop appear to be unambiguous sources of this southern admixture in ancient Eastern Europe. That's because the Caucasus Maykop mtDNA profile still looks somewhat off in this context, while steppe Maykop harbors West Siberian forager-related genome-wide ancestry that is practically absent in the Yamnaya and all other closely related peoples. In any case, please note the happy coincidence that academia has finally caught up to this blog and managed to find European farmer-derived ancestry in Yamnaya:

Importantly, our results show a subtle contribution of both Anatolian farmer-related ancestry and WHG-related ancestry (Fig.4; Supplementary Tables 13 and 14), which was likely contributed through Middle and Late Neolithic farming groups from adjacent regions in the West. A direct source of Anatolian farmer-related ancestry can be ruled out (Supplementary Table 15). At present, due to the limits of our resolution, we cannot identify a single best source population. However, geographically proximal and contemporaneous groups such as Globular Amphora and Eneolithic groups from the Black Sea area (Ukraine and Bulgaria), which represent all four distal sources (CHG, EHG, WHG, and Anatolian_Neolithic) are among the best supported candidates (Fig. 4; Supplementary Tables 13,14 and 15).Check out what I had to say about this issue exactly two years ago: Yamnaya = Khvalynsk + extra CHG + maybe something else. Not bragging, just making a point that I do know what I'm doing here, most of the time anyway. Wang et al. conclude their preprint with, unfortunately I have to say, some downright bizarre comments in regards to the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) homeland debate. But I'll get back to that later, when the ancient data from this and forthcoming related papers are released online. Citation... Wang et al., The genetic prehistory of the Greater Caucasus, bioRxiv, posted May 16, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/322347 See also... Yamnaya: home-grown Ahead of the pack Genetic borders are usually linguistic borders too

New PCA featuring Botai horse tamers, Hun and Saka warriors, and many more...

Just in case anyone's wondering how the ancient samples from the two recent archaeogenetic papers by Damgaard et al. (Nature and Science) behave in my two main Principal Component Analyses (PCA), here you go:

The relevant datasheet is available here. Just over 100 of the new samples made into onto this plot, but to keep things simple I only highlighted a few of them. To see the positions of any or all of the rest, plug the datasheet into, say, PAST (freely available here) and create your own version of the plot. Also, below are links to updated Global25 datasheets, featuring coordinates for almost all of the new samples (available separately here).

Global25 datasheet ancient scaled Global25 pop averages ancient scaled Global25 datasheet ancient Global25 pop averages ancientThe interesting thing about those Tian Shan nomads, especially the Kangju people, is that they're much more West Eurasian (European + West Asian) than the Asian Scythians sampled to date. However, despite this, they're still no good for modeling the West Eurasian ancestry of most South Asian populations. I've looked at this closely, and the Steppe_MLBA cluster is still the one to beat in this respect. See also... Genetic ancestry online store (to be updated regularly)

Sunday, May 13, 2018

Hittite era Anatolians in qpAdm

The apparent lack of steppe ancestry in five Hittite era, perhaps Indo-European-speaking, Anatolians was interpreted in Damgaard et al. 2018 as a major discovery with profound implications for the origin of the Anatolian branch of Indo-European languages.

But I disagree with this assessment, simply because none of these Hittite era individuals are from royal Hittite, or Nes, burials. Hence, there's a very good chance that they were Hattians, who were not of Indo-European origin, even if they spoke the Indo-European Hittite language because it was imposed on them.

Moreover, I am actually seeing a minor, but persistent, signal of steppe ancestry in one of the two Old-Hittite Period (~1750–1500 BCE) samples: Anatolia_MLBA MA2203. Indeed, I can put together very coherent, chronologically sound models using a couple of different methods to demonstrate this. Below is a fairly decent qpAdm model.

Anatolia_MLBA_MA2203 Anatolia_EBA 0.794±0.073 Ukraine_Eneolithic_I6561 0.206±0.073 tail: 0.400704 Full outputObviously, these numbers aren't exactly impressive. But if the signal is real, then it might be an indication of things to come when someone manages to sequence at least a few genomes from confirmed Hittite remains. None of the other Anatolia_MLBA individuals, three of whom are from the Assyrian Colony Period (~2000–1750 BCE), show such obvious steppe ancestry.

Anatolia_MLBA_MA2200 Anatolia_EBA 1.000 Ukraine_Eneolithic_I6561 0.000 tail: 0.449485 Full output Anatolia_MLBA_MA2205 Anatolia_EBA 0.983±0.069 Ukraine_Eneolithic_I6561 0.017±0.069 tail: 0.618499 Full output Anatolia_MLBA_MA2206 Anatolia_EBA 0.868±0.089 Ukraine_Eneolithic_I6561 0.132±0.089 tail: 0.708811 Full output Anatolia_MLBA w/o MA2203 Anatolia_EBA 1.000 Ukraine_Eneolithic_I6561 0.000 tail: 0.286377 Full outputIn any case, apart from all of that, Damgaard et al. do take a measured and sober approach to interpreting their archaeogenetic data in the context of the Indo-European homeland debate. The paper also includes a very thorough linguistic supplement, freely available here, which reveals that there is Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) ancestry in soon to be published Maykop culture samples. From the supplement (emphasis is mine):

Despite a general agreement on a Pontic-Caspian origin of the Anatolian Indo-European language family, it is currently impossible to determine on linguistic grounds whether the language reached Anatolia through the Balkans in the West (Anthony 2007; Mallory 1989: 30; Melchert 2003; Steiner 1990; Watkins 2006: 50) or through the Caucasus in the East (Kristiansen 2005: 77; Stefanini 2002; Winn 1981). From their earliest attestations, the Anatolian languages are clustered in Anatolia, and if the distribution reflects a prehistoric linguistic speciation event (as argued by Oettinger 2002: 52), then it may be taken as an indication that the arrival and disintegration of Proto-Anatolian language took place in the same area (Steiner 1981: 169). However, others have reasoned that the estimated period between the dissolution of the Proto-Anatolian language and the attestation of the individual daughter languages is extensive enough to allow for prehistoric mobility within Anatolia, theoretically leaving plenty of time for secondary East-to-West dispersals (cf. Melchert 2003: 25). Whatever the case may be, there are no linguistic indications for any mass migration of steppe-derived Anatolian speakers dominating or replacing local populations. Rather, the Anatolian Indo-European languages appear in history as an organically integrated part of the linguistic landscape. In lexicon, syntax, and phonology, the second millennium languages of Anatolia formed a convergent, diffusional linguistic area (Watkins 2001: 54). Though the presence of an Indo-European language itself demonstrates that a certain number of speakers must have entered the area, the establishment of the Anatolian Indo-European branch in Anatolia is likely to have happened through a long-term process of infiltration and acculturalization rather than through mass immigration or elite dominance (Melchert 2003: 25). Furthermore, the genetic results presented in Damgaard et al. 2018 show no indication of a large-scale intrusion of a steppe population. The EHG ancestry detected in individuals associated with both Yamnaya (3000–2400 BCE) and the Maykop culture (3700–3000 BCE) (in prep.) is absent from our Anatolian specimens, suggesting that neither archaeological horizon constitutes a suitable candidate for a “homeland” or “stepping stone” for the origin or spread of Anatolian Indo-European speakers to Anatolia. However, with the archaeological and genetic data presented here, we cannot reject a continuous small-scale influx of mixed groups from the direction of the Caucasus during the Chalcolithic period of the 4th millennium BCE. ... Under the “Steppe Hypothesis,” the Indo-Iranian languages are not seen as indigenous to South Asia but rather as an intrusive branch from the northern steppe zone (cf. Anthony 2007: 408–411; Mallory 1989: 35–56; Parpola 1995; Witzel 1999, 2001). Important clues to the original location and dispersal of the Indo-Iranians into South and Southwest Asia are provided by the Indo-Iranian languages themselves. The Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages share a common set of etymologically related terms related to equestrianism and chariotry (Malandra 1991). Since it can be shown that this terminology was inherited from their Proto-Indo-Iranian ancestor, rather than independently borrowed from a third language, the split of this ancestor into Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages must postdate these technological innovations. The earliest available archaeological evidence of two-wheeled chariots is dated to approximately 2000 BCE (Anthony 1995; Anthony and Ringe 2015; Kuznetsov 2006: 638–645; Teufer 2012: 282). This offers the earliest possible date so far for the end of Proto-Indo-Iranian as a linguistic unity. The reference to a mariannu in a text from Tell speakers. Leilān in Syria discussed below pushes the latest possible period of Indo-Iranian linguistic unity to the 18th century BCE. ... The traces of early Indo-Aryan speakers in Northern Syria positions the oldest Indo-Iranian speakers somewhere between Western Asia and the Greater Punjab, where the earliest Vedic text is thought to have been composed during the Late Bronze Age (cf. Witzel 1999: 3). In addition, a northern connection is suggested by contacts between the Indo-Iranian and the Finno-Ugric languages. Speakers of the Finno-Ugric family, whose antecedent is commonly sought in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains, followed an east-to-west trajectory through the forest zone north and directly adjacent to the steppes, producing languages across to the Baltic Sea. In the languages that split off along this trajectory, loanwords from various stages in the development of the Indo-Iranian languages can be distinguished: 1) Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian (Proto-Finno-Ugric *kekrä (cycle), *kesträ (spindle), and *-teksä (ten) are borrowed from early preforms of Sanskrit cakrá- (wheel, cycle), cattra- (spindle), and daśa- (10); Koivulehto 2001), 2) Proto-Indo-Iranian (Proto-Finno-Ugric *śata (one hundred) is borrowed from a form close to Sanskrit śatám (one hundred), 3) Pre-Proto-Indo-Aryan (Proto-Finno-Ugric *ora (awl), *reśmä (rope), and *ant- (young grass) are borrowed from preforms of Sanskrit ā́ r ā- (awl), raśmí- (rein), and ándhas- (grass); Koivulehto 2001: 250; Lubotsky 2001: 308), and 4) loanwords from later stages of Iranian (Koivulehto 2001; Korenchy 1972). The period of prehistoric language contact with Finno-Ugric thus covers the entire evolution of Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian into Proto-Indo-Iranian, as well as the dissolution of the latter into Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian. As such, it situates the prehistoric location of the Indo-Iranian branch around the southern Urals (Kuz’mina 2001).Citation... Guus Kroonen, Gojko Barjamovic, & Michaël Peyrot. (2018). Linguistic supplement to Damgaard et al. 2018: Early Indo-European languages, Anatolian, Tocharian and Indo-Iranian. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1240524 Update 14/05/2018: I managed to, more or less, reproduce my qpAdm models with qpGraph. This is never a simple and easy task, so I'm now more confident that Anatolia_MLBA MA2203 really does harbor ancestry from the steppe. See also... Likely Yamnaya incursion(s) into Northwestern Iran Graeco-Aryan parallels Late PIE ground zero now obvious; location of PIE homeland still uncertain, but...

Thursday, May 10, 2018

Graeco-Aryan parallels

The clearly non-local admixture in the geographically and genetically disparate, but Indo-European-speaking, ancient Mycenaeans and present-day North Indian Brahmins is very similar. So similar, in fact, that it could derive from practically the same population in space and time. The most plausible source for this admixture are the Bronze Age herders of the Pontic-Caspian steppe and their immediate descendants, such as those belonging to the Sintashta and other closely related archaeological cultures.

To prove and simultaneously illustrate this point, below are a couple of Admixture graph or qpGraph analyses. Note that I was also able to add Balkans_BA I2163 to the Mycenaean model. This is an Srubnaya-like ancient sample from the southern Balkans dating to the early Mycenaean period. Not only does Balkans_BA I2163 help to further constrain the model, but it also suggests a proximate source of steppe-related admixture into the population that potentially gave rise to the Mycenaeans. The relevant graph files are available here.

Considering that the Bronze Age peoples of the Pontic-Caspian steppe are the only obvious and direct, and, hence, most plausible link between the Mycenaeans and Brahmins, it follows that they are also the most likely vector for the spread of Indo-European speech to ancient Greece and South Asia. Or not? But if not, then what are the alternatives, and I mean real alternatives, not just excuses? If you think that you can offer a genuine alternative then feel free to do so in the comments below. However, be warned, stupid sh*t won't be tolerated.

See also...

Main candidates for the precursors of the proto-Greeks in the ancient DNA record to date

On the doorstep of India

Steppe admixture in Mycenaeans, lots of Caucasus admixture already in Minoans (Lazaridis et al. 2017)

Monday, May 7, 2018

Protohistoric Swat Valley peoples in qpGraph #2

Three options. Just one passes muster; the one with Sintashta. Coincidence? I think not. Who still wants to claim that there's no Sintashta-related steppe stuff in these Iron Age SPGT South Asians? The relevant graph files are available here. Any ideas for better models?

Update 08/05/2018: The reason that I chose Dzharkutan1_BA, from what is now Uzbekistan, as the BMAC proxy in the above graphs was because it's geographically a proximate choice for SPGT. However, I've since discovered that Gonur1_BA, from what is now Turkmenistan, does a somewhat better job in these models. The additional graph files are available at the same link as above here.

See also...

Protohistoric Swat Valley peoples in qpGraph

The protohistoric Swat Valley "Indo-Aryans" might not be exactly what we think they are

Friday, May 4, 2018

The protohistoric Swat Valley "Indo-Aryans" might not be exactly what we think they are

I need some help interpreting these linear models of ancient and present-day South Asian populations. Overall, the Iron Age groups from the Swat Valley, or SPGT, look like rather obvious outliers. The relevant datasheet is available here.

The reason for this might be significant bidirectional gene flow and/or continuity between Central Asia and the northern parts of South Asia before Sintashta-related steppe herders showed up in the region, and even before the Bactria Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) got going. Note that Dzharkutan1_BA is an BMAC sub-population from near South Asia, but it doesn't quite have the same effect on those Swat Valley samples as the pre-BMAC Shahr_I_Sokhta_BA1 from the present-day Iranian/Afghan border.

If true, it probably means that most of the Iron Age peoples of the Swat Valley shouldn't be modeled as simply a mixture of Indus_Periphery and Steppe_MLBA. That's because they appear to be in part of the same or similar type of ancestry as Shahr_I_Sokhta_BA1. And indeed, qpAdm also suggests that they are.

SPGT Indus_Periphery 0.692±0.042 Shahr_I_Sokhta_BA1 0.104±0.045 Sintashta_MLBA 0.204±0.015 taildiff: 0.659609 Full outputI'm trying to incorporate this new information into my Admixture graph models of the SPGT groups (see here). If I manage to come up with something useful I'll update this post with the results. Update 08/05/2018: see here.

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

Open analysis thread: genetic distance (Fst) matrix focusing on ancient Central and South Asia

I'm hoping that we can learn something new about the genomic prehistory of Eurasia, and especially Central and South Asia, based on this massive new Fst matrix:

Ancient Central and South Asia genetic distance (Fst) matrixHint: it's probably easiest to initially explore this format with a program called PAST. Indeed, if you'd like to model fine scale ancestry proportions based on these data, it might be a good idea to use PAST to first turn the matrix into a principal coordinates (PCoA) datasheet (like this). On a related note, as I was typing this, commentator Chetan alerted me to a post at the Molgen forum claiming that Y-haplogroup R1b-L51 has turned up in Eneolithic remains from Pontic-Caspian steppe (see here). If true, then it's a big deal, because it's the best evidence yet that L51 expanded into Central and Western Europe from the steppes. This is the Google translation of the post. Emphasis is mine.

Hello. Today, the XIV Samara Archeological Conference was held. The following reports were heard. Khokhlov AA Preliminary results of anthropological and genetic studies of materials of the Volga-Ural region of the Neolithic-Early Bronze Age by an international group of scientists. In his report, AA Khokhlov. introduced into scientific circulation until the unpublished data of the new Eneolithic burial ground Ekatirinovsky cape, which combines both the Mariupol and Khvalyn features, and refers to the fourth quarter of the V millennium BC. All samples analyzed had a uraloid anthropological type, the chromosome of all the samples belonged to the haplogroup R1b1a2 (R-P 312 / S 116), and the haplogroup R1b1a1a2a1a1c2b2b1a2. Mito to haplogroups U2, U4, U5. In the Khvalyn burial grounds (1 half of the 4th millennium BC), the anthropological material differs in a greater variety. In addition to the uraloid substratum, European broad-leaved and southern-European variants are recorded. To the game haplogroup R1a1, O1a1, I2a2 are added to mito T2a1b, H2a1.I'd say that this information sounds legit. But let's wait and see if the results are backed up by one of the major ancient DNA labs in the west, like the Reich Lab. See also... Late PIE ground zero now obvious; location of PIE homeland still uncertain, but...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)